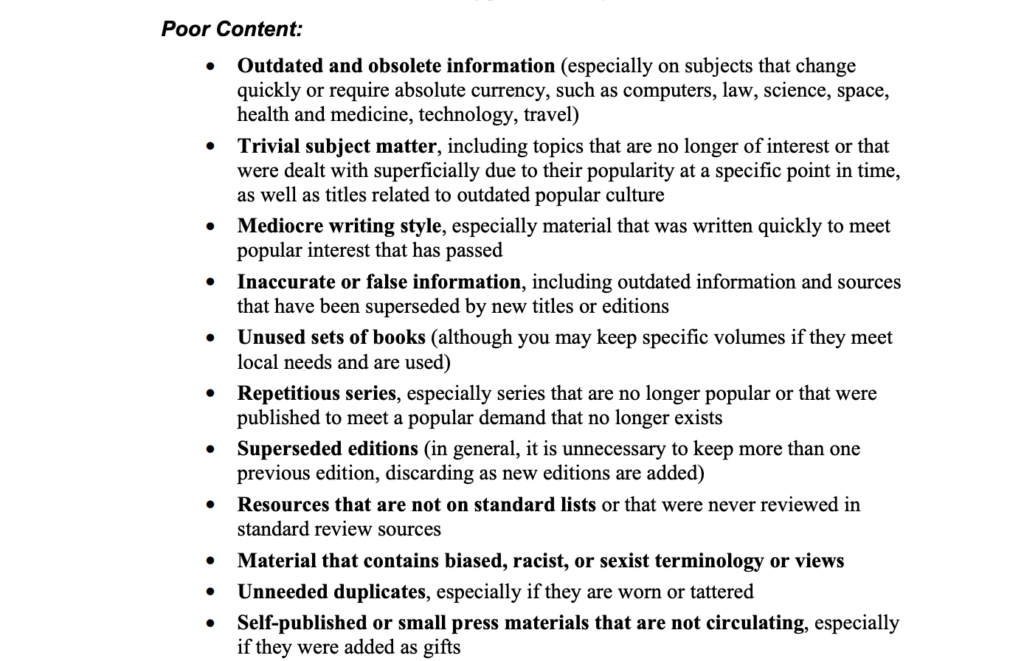

Even trickier is the fact many libraries are seeing the copies of the six books they do own go “missing.” Organizations like the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC), ostensibly committed to “freedom of thought, inquiry, and expression,” have been among the groups pushing back against the decision made by Seuss Enterprises. Despite the fact this was a business decision — not all books can be in print forever, nor should they be — coupled with facing the painful realities of the racist depictions within the books, NCAC’s response proved that the business of book selling, as opposed to censorship nor the harm books like these bring to readers, is their actual mission: Statements like this only further muddy the waters of the mission and goals of public libraries and what their responsibility is relating to books like these. NCAC believes in preserving books that even the organization dedicated to upholding a beloved author’s legacy has deemed racist is necessary. In doing so, they fundamentally misunderstand the purpose of libraries as well. Our society is in the midst of a broad conversation about the racism embedded in many of our cultural touchstones. We need to acknowledge that many of the books that are part of America’s literary heritage express attitudes about race that may offend people. Almost all authors are influenced by the prejudices of their times. Dr. Seuss is no exception. However, we must draw a line between criticizing texts and purging them. If we remove every book that is offensive to someone, there will be very little left on the shelf. NCAC supports and celebrates efforts to diversify library holdings, expand the stories told through school curricula and encourage underrepresented voices to be heard. While we cannot ignore the insidious effect of allowing children to uncritically encounter embedded racism in the books they read, we should not expunge those books from the culture as a whole. It is important to preserve our literary heritage even when it reflects attitudes that are no longer tolerated as they once were. If nothing else, books like those that have been dropped by Dr. Seuss Enterprises show us how important it is to read critically and temper our admiration for beloved authors with the knowledge that they are often flawed human beings. So what does a library do? The good news is, there’s a simple solution. One of the responsibilities of public libraries is to maintain a collection development policy, which outlines the kinds of materials purchased with the budget, as well as the decision making that goes into removing books from a collection. One of the techniques most commonly used by libraries in the US is the CREW method. This freely-available manual was created by the Texas State Library and Archives Commission and is updated when appropriate. The latest edition, for example, includes guidelines for where and how to update ebooks. The CREW method was developed in 1976 with the goal of helping small and mid-sized libraries which have limited staff and budget to keep their collections as relevant as possible. It’s since grown in usefulness, and it’s a standard tool even among larger libraries. As it states in the introduction, “CREW: A Weeding Manual for Modern Libraries attempts to describe clearly, practically, and in a step-by-step fashion a now tried-and-true method of carrying out the five processes of ‘reverse selection:’ inventory, collection evaluation, collection maintenance, weeding, and discarding.” MUSTIE is the quick and dirty acronym used with the CREW method for determining material needing to be evaluated in libraries: Misleading/factually incorrect material/poor content; Ugly/worn beyond repair; Superceded/there’s a new edition or a better book on the topic; Trivial/of no discernible literary, scientific, or cultural merit; Irrelevant to the needs or interests of the library community (this in particular explains why some books are readily available in one library but may not be in a library in another community); and finally, Elsewhere/the material is easy to obtain from another library for those seeking it out. It’s under the very first criteria — Misleading/factually incorrect material/poor content — where the CREW method explicitly states racist material is something to weed. Racist material is poor content, and in the case of these six Dr. Seuss books, the parent company’s decision to cease reprints due to their racist illustrations gives libraries any and all necessary proof of why the books need to be weeded. No, this doesn’t mean pulling Green Eggs and Ham nor The Cat in the Hat, both books which have long circulation histories, as well as remain perennial favorites in many communities. What it does mean is that And To Think I Saw it On Mulberry Street, If I Ran The Zoo, McElligot’s Pool, On Beyond Zebra!, Scrambled Eggs Super!, and The Cat’s Quizzer are ready to be decommissioned. Libraries which still have those titles among their holdings likely weren’t seeing much circulation of them prior to March 2, and with clear and direct admission of what’s inside those books from the organization responsible for publishing them, there’s no excuse to keep them around. It’s not censorship. It’s responsible collection curation. It’s not censorship. It’s being accountable to your community, which is comprised of people from a myriad of backgrounds. It’s not censorship. It’s accountability. Libraries are in a unique position here to be leaders, rather than followers by adhering to their own guidelines when it comes to what’s held within their stacks. Organizations like NCAC have it wrong — and they’ll continue to have it wrong as long as they fail to understand the purpose of the library, as well as when they have the book business as their priority. Their statement isn’t about helping readers or preserving literary heritage. It’s about the bottom line when it comes to making a buck. And libraries don’t have that as their central mission. They have serving their communities at the forefront, and to be leaders in doing just that, those six books need to be discarded.