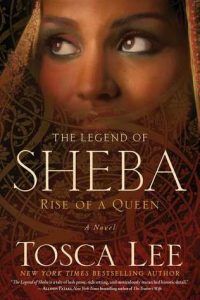

Historically, the figure of the Queen of Sheba is shrouded in obscurity, which all but facilitates its becoming a cultural repository of all the dreams and glittering gold-tinted notions we have of the exotic East. She appears in the Quran and the Ethiopian Kebra Nagast, and the Bible mentions her a few times; she is the ‘Queen of the South’ who ‘came from the ends of the earth to hear the wisdom of Solomon’ (Luke 11:31) and after that was so awed that she blessed his God (2 Ch 9:8). Sheba, or Saba, believed to be present-day Yemen or/and Ethiopia, was a land rich with gold, frankincense and myrrh, deriving its wealth from trade along the Incense Route. Tosca Lee makes this world come alive with its caravans and traders and Desert Wolves, hardened nomads bound to no king or kingdom, and whom at heart Bilqis, tethered as she is to her throne and its responsibilities, yearns to be. Solomon is more well-known. To Christians he is the king who pleased God by asking for wisdom, but who swelled complacent on the blessings of God and let his foreign wives turn his heart to other gods (1 Kings 11). His extravagance, lust, idolatry and oppression of his people eventually brought about his kingdom’s downfall. Lee turns this sage-king into a man and a boy, flawed and broken; one who cannot recover the first blush of his love for God and so wanders lonely and empty and lost, trying to slake his insatiable thirst through his endless accrual of wealth. In Lee’s story Solomon’s thousand concubines, and his building of grand temples to their gods, are not so much signs of his lust and idolatry, but an understandable way to expand trade through alliances. He doesn’t think his acts a sin, insisting that he still worships Yahweh in his heart. This is a Solomon so torn by his wisdom that in the end he calls himself a fool. That’s why he argues with such desperation, each argument he flings out leaving him more desolate than before; because by argument every sin can be justified or condemned. That’s why he treasures his prophet for standing up to him, because he struggles to hear the one clear voice of God amid his turmoil of logic. He is constantly in search of mystery because he thinks that in each one he pursues and solves he may find an answer to the abyss in himself. Bilqis sees in him a mirror of herself, and they correspond via letters that take six months or longer to arrive, each intriguing and aggravating the other with their wit, hauteur, and finally their touching candour and yearning. When Sheba is forced to make the long, hard journey across the sands to visit Israel, she thinks she only wants to discuss treaties, but then begins her short-lived but passionate love affair with the king that is all the more beautiful because we know it must end. Ultimately it is Bilqis who tells Solomon that he has broken fidelity with Yahweh, because he has made his kingdom a substitute for God. If he is guilty of any idolatry it is to conquest itself. Even as he worships the God whose ‘name is love’, it is his kingdom, literal and figurative, that he is unable to surrender, that he loves more than any woman, that he ceaselessly hungers to expand. It is the consuming hunger of man. Bilqis recognises that this is a hunger that she will never be able to satisfy. But Bilqis is not a man. She learns to let go, and so finds freedom earlier than Solomon, who only enters their dream of Edenic bliss in death, a vision that Bilqis painted for him in one of her early letters: